Every year, my family and I load up our car with freezer bags and make the one hour trek to Carrollton to stock up on Japanese food. The bulk of our haul is done at H Mart, a Korean supermarket, where we scour each aisle for foods that we won’t be able to get for another few months. Our outing ends with fatigue, a $300 grocery bill and sore arms from grocery bags on the verge of breaking with the weight of all the food. Despite the negative side-effects, the trip became a family tradition and necessary for us to maintain our culture in my household.

So to say I was angry when I saw non-Asian people start coming to H Mart for the sole purpose of taking pictures in the drink aisle and buying select snacks, would be a complete understatement.

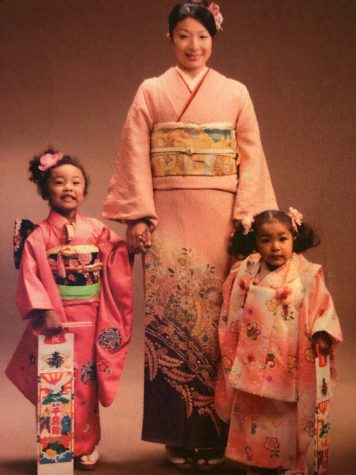

Watching all of these foods gain popularity has exemplified my experience as an Asian American. People pick and choose the acceptable parts of my culture through the commodification of stereotypes and demonize or sexualize the rest of it. The kimono, the traditional japanese dress identified by its distinctive rectangular silhouette and extended square sleeves, has now been rebranded into a silk robe with floral designs by western culture (or shapewear by Kim Kardashian). On the other hand, geishas, women who are trained in traditional Japanese performance arts, are very commonly associated with prostitution in the West because of the prostitution occuring in Japan during WWII. Or now, the popularization and praise of snacks such as Pocky and rice crackers, yet the disgust of foods like natto or umeboshi.

The aestheticization of Japan has made it incredibly hard to identify with my culture. I don’t watch anime, yet people who have binged shows of the genre feel more entitled to identify with being Japanese than I do. But when it comes to the rise of hate crimes, the same people who partake in ‘weeb’ culture suddenly go silent.

The possibility of one of my parents dying at the hands of racism has not been a far off fear. My Black father takes extensive road trips for his job and the chance of a routine stop going wrong always haunts me. But now, I have to wonder if my mom will come back home after buying groceries.

The whole point of cultural appropriation is that it is purely convenient for those who partake in it. They may wipe off their suspiciously winged liner, but I cannot hide my eyes. The same eyes that make me a target for a potential hate crime. Though considerable strides have been made in recognizing the rise of hate crimes against the Asian community, it’s still not enough. Until the day I can feel confident in stepping outside without the potential of getting hurt or being associated with derogatory stereotypes, recognition isn’t enough.