A bright sun shimmers overhead in the clear blue sky. Senior Haley Hines looks up to admire it from between the reef walls, 50 feet below the surface of the Caribbean Ocean. Twenty feet away a Caribbean squid floats in the water, and stoplight parrotfish root around below him in the sand. Bright staghorn coral and basket sponge decorate the reef, disguising lionfish and providing a home for other aquatic life. Hines floats along beside the myriad of aquatic creatures, hearing nothing but her own breathing and admiring the tranquility of the ocean life at Sunset Reef.

Scuba diving boomed into popularity during the 1970s and continues to stay a prominent recreational activity. Hines earned her open water diving certification during the summer of 2014 while on vacation in the Cayman Islands.

“If you like to swim and you’re interested in seeing more than what you see at the surface, you should try diving,” Hines said. “Seeing everything — all the fish, all the conch, sea urchins and eels — in their natural habitat is amazing.”

Scuba Schools International (SSI) Diver sophomore John Drake received inspiration to dive while on vacation in Jamaica. Drake observed other divers and became overwhelmed with the desire to experience the ocean in a way only divers can.

John Drake, 10, gestures to Chick-fil-A merchandise while scuba diving in Punta Cana, Dominican Republic.

“When you dive you feel weightless,” Drake said. “You have a sense of wonder.”

Senior Samuel Berbel tested out diving after his father regaled him with stories from his own diving experience as a Divemaster in Latin America. Berbel gained his PADI Open Water Diver certification in 2012.

“It’s the closest thing to weightlessness,” Berbel said. “It’s almost like floating. You’re not tied down to anything; it’s more freeing than anything I can describe.”

Before a person dives, they must first be certified. The most well-known scuba certification company, Professional Association of Diving Instructors (PADI), teaches divers how to properly use equipment such as weight belts (nylon belts with as many two-pound weights a person needs to counteract the salt water) and buoyancy control devices (BCDs) to remain neutrally buoyant in the water. History teacher Ms. Shelene Anderson, Hawaii Pacific University alumna, began diving at the age of 19 when she needed a P.E. credit for college.

“For me, the best thing about diving is getting to see things some people can’t even imagine,” Ms. Anderson, an Advanced PADI Open Water Diver, said. “But it’s also good to feel like a mermaid.”

Divers become certified at the average age of 29. Divers that begin in high school get a head start on others.

Senior Chelsey Malone plans on adding herself to the long list of PADI divers during the summer of 2015.

“I really like ocean life,” Malone said. “To go down and see all that would be amazing and relaxing. It’s not too dangerous, but it still has a thrill factor.”

While scuba diving does occasionally present dangerous situations, divers cause most scuba injuries themselves. In 2006, the Divers Alert Network (DAN) reported 138 diving deaths worldwide. Most recorded incidents divers inflicted themselves due to recklessness or ignorance.

Berbel’s run-in with fire coral demonstrates a situation where a diver’s ignorance causes harm. While diving in Cancún, Berbel brushed his leg against the coral, resulting in a painful stinging sensation. Luckily, Berbel’s father showed him how to use slime secreted from brain coral to lessen the sting.

“[The fire coral] was the most frightening thing,” Berbel said. “But I was able to finish the dive in only mild discomfort.”

Diving behaviors that exhibit recklessness include misusing equipment or trying to pet or feed an underwater creature, indirectly causing an injury. A famous rule from PADI’s Open Water Diver course states that “if it’s very pretty, very ugly or unafraid of you, stay away from it.”

“I think [that rule] holds true to everything,” Berbel said. “Some things are very pretty but dangerous to touch, like fire coral.”

None of the divers experienced any serious injury while diving, but there have been a few unlucky strokes. Ms. Anderson experienced a close call when the air hose that inflated her BCD detached. The loss of air and her 12-pound weight belt caused her to become a dead weight in the water and start to sink. Her dive buddy began to direct them back to shore, but to Ms. Anderson’s dismay, her buddy lead them the wrong way right into a rocky cliff. Ms. Anderson then escorted her buddy back to shore while struggling to stay up in the water.

“At first I was panicked; I thought I was gonna drown,” Ms. Anderson said. “I was just thinking I need to get [to shore] before my air runs out. It was a lot of work, and I was exhausted. In retrospect, it’s one of those funny things you can laugh about. It wouldn’t make me give up diving ever; under the water is wonderful.”

Hines joined Ms. Anderson as a victim of broken equipment the day after she passed her certification test. While 40 feet underwater on her first real dive, the strap on her mask broke. Hines had to clear the water from her mask to see before making an emergency ascent to the surface.

“I was slightly agitated that my mask broke,” Hines said. “I had to end the dive before I was done.”

Great barracudas frequent tropical waters such as Cancún, where Berbel’s family saw one on a wreck dive. Berbel himself did not see the barracuda and expressed his relief in not spotting it after later hearing about it from his father when they surfaced.

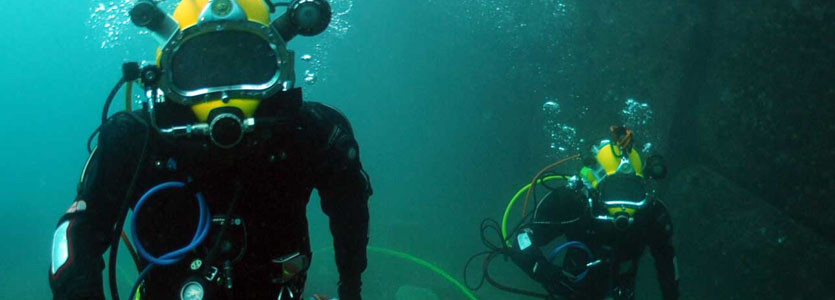

Samuel Berbel, 12 (left in foreground) dives with his family in Cancún.

“I’m glad I didn’t see it,” Berbel said. “I wouldn’t have enjoyed the dive.”

For many divers, the experience far outweighs the risks. Despite encounters with barracudas, fire coral and broken equipment, their love of the sea has not diminished.

“We know more about other planets than our own ocean,” Berbel said. “[When] you get to explore the ocean it’s really amazing.”

Hines recounts her favorite diving experience as the time she first encountered garden eels. Garden eels live with their lower half buried in the sand. Gently swaying in the current, their small and thin bodies can easily be mistaken for seaweed.

“When you swim over them they sink down into the sand,” Hines said. “An entire field of garden eels parts before you like they’re bowing down.”

Drake’s best experience diving came when he and his uncle swam alongside a sea turtle and lionfish on a reef in Jamaica. Berbel treasures the memory of his first wreck dive in Cancún, where he watched schools of fish swimming around an artificial reef and through the wrecked ship. Ms. Anderson remembers the time she went on a night dive in Hawaii.

“If you dive at nighttime, you get to see all the critters that glow,” Ms. Anderson said.

The scuba divers have all adored their experiences underwater. All of them would recommend diving to another person, despite any anxiety they may feel.

“First you get nervous, because you want everything to go right and you have so much to remember,” Ms. Anderson said. “But once you are underwater, you don’t worry; you just relax and get to see all these amazing creatures.”

(Photo by U.S. Navy)

David Duke AKA GrandPa • Jan 22, 2015 at 8:04 pm

Very interesting Story Heather. You did a fine reporting something I have never done. Although at Lake Whitney has a Dive Shop and watched the class practiced in the parking lot. They were practicing with a towel over their Heads so they couldn’t see. Love your story telling! Hugs Grandpa!

and you are doing a good job.