As she plants her foot in the ground, junior Brenna Scheffler grimaces at the pain that shoots through her leg during a sprint at practice. She experiences what feels like fireworks popping throughout her thigh but shrugs it off and catches back up with her soccer teammates. Scheffler tore her quad, but keeps to herself in hope that it’s not severe.

Although injuries in sports present enough danger by themselves, training for them or overtraining can also have harmful effects. One case of an overworked athlete could happen during a workout. At the University of Maryland, Jordan McNair, a 19-year-old football player, collapsed during one of the team’s summer workouts on June 13, 2018. He died from extreme exhaustion. But at Legacy, Scheffler thinks student-athletes receive similar harsh training.

“I definitely think we’re pushed too hard. Almost every girl, if not every girl, plays outside of school too, and [the coach] knows that. It’s almost like he doesn’t even take it into consideration,” Scheffler said. “It’s obviously way too much.”

Sophomore and varsity football player David Abiara thinks the problem lies in a person’s mindset.

“[The coach’s] job is to push us to our max,” Abiara said. “It helps get us faster and to be beasts on the field.”

At Legacy, no over-exhaustion related accidents have occurred. Chris Melson, Athletic Director, thinks overextension of athletes occurs outside of the school.

“[Athletes] can overtrain, but I don’t think our coaches do,” Coach Melson said. “When you have [others] on the outside working kids out and doing their own little thing, then that’s the issue. We always want kids to have good rest and healthy bodies. But all that working outside could lead to issues.”

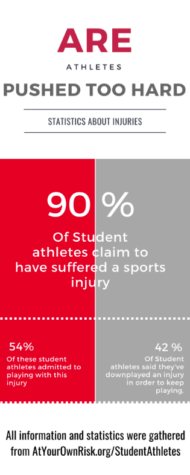

Pushing athletes too hard can also come from players who continue to play through injuries. Almost 2 million high school athletes have to come out of play with an injury each year. 62 percent of these injuries occur during practice, where athletes tend to take less initiative to have the proper safety. Abiara speaks of possible precautions athletes could do to stay safe.

“We tape our wrists and our ankles to prevent any more injuries, and we also stretch before practice to loosen up,” Abiara said. “We can gauge how severe an injury is, and depending on if it’s bad or not, we’ll either go to the trainers or just play through it.”

After an athlete gets hurt they report to an orthopedic and bring results back to their coach. Depending on how minor or major the injury, the coach and player either agree on a day to come back to play or encourage the athlete to tough through it. According to Abiara, the impact a player could have toward the benefit of the team would override any injury.

“It’s what’s best for the team. I feel like sometimes players might not be healed all the way, but [playing] is what’s for the team,” Abiara said. “I’m not against it at all. I’m actually for it, like if you can play, then you should play. Unless it’s something serious, then you can sit out”

However, Scheffler believes coaches and teammates just stereotype athletes’ complaints as an excuse not to play or as a weakness.

“[The coach] would never make us play, but there’s definitely some pressure to perform. I’ve had six concussions,” Scheffler said. “And that was definitely taken pretty seriously, but, after a while, people started thinking I was milking it.”

Of the 30 million youth athletes who play sports, about 3.5 million reported to have an injury at some point in time. But in sports, injuries go further than minor bumps and bruises and Scheffler admits the serious accidents of the game plays with an athlete’s mind.

“Knowing the sport I play can be such a physical sport definitely scares me. I know that every time I step on the field there’s a chance that I could tear a muscle or break a bone,” Scheffler said. “But I don’t let that stop me. I’ve had multiple concussions, each one worse than the one before, but I continue to play like it never happened because I love this game.”