Miami Dolphins quarterback Tua Tagovaloa lays on the ground, fingers clenched, unable to move. Twitter goes up in flames criticizing the Dolphin’s training staff for allowing Tagovailoa to play the week four matchup against the Cincinnati Bengals just four days after sustaining a concussion.

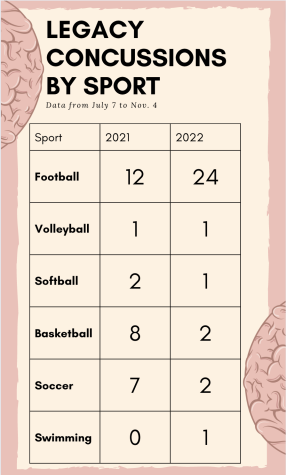

Entering week nine of the NFL season, there have been 69 diagnosed concussions. From July 1 to Nov. 4, Legacy athletics identified 31 concussions in student-athletes. In comparison, Legacy had 30 total concussions last year and only 15 in this span of time. These numbers include all concussions caused by sports and non-sport-related injuries. Ms. Kassey Newton, athletic trainer, attributes this to heightened awareness about concussions.

“The more that you bring attention and knowledge to an issue, people start paying more attention to it and I don’t necessarily think it’s a bad thing,” Ms. Newton said. “I also think that the recognition of it is rising from coaches to athletes, and athletes [are] reporting on each other which is actually a good thing. People are more forthcoming with it.”

The CDC defines a concussion as a “traumatic brain injury caused by a bump, blow, or jolt to the head that causes the brain to move rapidly back and forth.” Ms. Newton uses a simple metaphor to describe what a concussion does to the brain.

“Think of an egg inside of a shell [that has] yolk. If you shake that egg up, you’ve now scrambled it,” Ms. Newton said. “The yolk is the representation of your brain, so when your brain hits the wall of your skull, it’s like a bruise on the brain.”

Once diagnosed with a concussion, Mansfield ISD athletes must complete a five-step concussion protocol to be returned to play. The protocol can begin after athletes are symptom-free, but if a concussed athlete shows any symptoms during protocol, it restarts.

“[Protocol is] a matter of you reducing those stimuli and taking your way out of bright environments, not reading or concentrating, focusing on things so you give your brain that time to rest and recover,” Ms. Newton said. “Then you gradually reintroduce those types of things and see how your brain responds to it. If you don’t get symptoms from trying to focus on reading or get symptoms from jogging, you ramp it up a little bit to increase your focus or activity. That’s what our return to play protocol is all about, that gradual progression back to activity.”

The NFL follows a similar protocol. After Tagovaloa’s injuries, the NFLPA, or NFL Players Association, revised the return to play policy to include the term “ataxia”. Ataxia results from damage to the cerebellum, or the area of the brain that controls muscle coordination, and causes clumsy movements. Junior Nathan Hanes not only suffered from a concussion in an August football game, but the same hit caused him to develop thoracic outlet syndrome and complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). Because of this, Hanes has been subject to ataxia for over two months and will undergo surgery on Nov. 18.

“[I have] more residual symptoms right now, but they were [bad],” Hanes said. “For me, it’s just laziness, grogginess, dizziness and sometimes I had trouble remembering.”

“[I have] more residual symptoms right now, but they were [bad],” Hanes said. “For me, it’s just laziness, grogginess, dizziness and sometimes I had trouble remembering.”

After suffering from one concussion, athletes are more susceptible to a second concussion, post-concussive syndrome and the sometimes fatal second impact syndrome. Post-concussive syndrome occurs when a concussion patient continues to have lingering months after the initial injury. Junior Luke Lansford suffered a concussion on Sept. 2 and was cleared a week after his initial blow. However, Lansford received a second concussion in the first practice after being cleared and has since developed post-concussive symptoms.

“I’ve been out for eight to nine weeks because the symptoms keep coming back and I just still have headaches and still get dizzy when working out,” Lansford said. “[When you have a concussion] everything feels off and you feel like you’re out of your body sometimes. You get really sensitive to everything and you’re just dizzy all the time.”

Because not all concussions have the same severity level, doctors created a three-stage grading scale. When a patient suffers the lowest degree concussion, a grade one, they do not lose consciousness and are most commonly seen in minor car accidents and sports injuries. Grade two concussions are very similar to grade one, but victims may briefly lose consciousness and may suffer from amnesia and vomiting. Grade three, the most dangerous, places patients at the highest risk for long-term brain damage and takes the longest to recover from.

“Concussion numbers are up everywhere,” Newton said. “This is what some people in the sports medicine world call a ‘concussion year’.”