Josh Powell didn’t know what to think. The surprise, three-hour drive to College Station gave him a long time to think bad thoughts. As the car sped 1 mile at a time closer to the site of the accident, it started to settle in for Josh that this could actually be something real.

In 1999, when Josh was a senior in high school, his mom picked up the phone early in the morning to hear that no one had been able to reach Josh’s brother, Chad, a freshman at Texas A&M. Chad wouldn’t pick up his phone. No one would.

Now Josh sat in the back seat of the car watching his worried mother in the passenger seat and his dad stare at the road ahead of him. His father’s unibrow scrunched from concentration and fear. His eyebrow is identical to Chad’s, something Josh used to give him a hard time for.

When the Powell family arrived on campus, the war room awaited them. A room full of families, Texas A&M University officials and emergency personnel spent hours searching for everyone who worked on the 59-foot high stack of wood for the upcoming bonfire when it collapsed at 2 a.m. Josh sat with his mother. His dad ran point, contacting all of the nearby hospitals, making calls to careflight and asking anyone who might know for news about Chad’s whereabouts and condition.

Amidst all of the chaos in the room, no one had real answers.

“No one knows where he is. No one has been able to find him. He has to be there,” Josh’s dad said.

Then the three, ignoring the warnings of the university officials, walked out of the room and across the field to the site of what once was a tall and proud bonfire stack. Josh feared for his brother, but he was terrified for his parents as they stopped within 150 yards of the wood pile.

An onsite emergency personal approached the Powells as they looked at the site of death, chaos and destruction.

“We think we found your son but we don’t know,” he said. “We need somebody to come identify him.”

Josh’s mother began crying next to him. Josh wanted to go see Chad’s body for himself.

“No you absolutely cannot go see him,” his father said. “I’ll go.”

Josh’s father disappeared around the other side of the pile. Awhile later, he returned.

“I’m pretty sure it is him,” he said. “His eyebrow is there.”

Josh stood right next to her when his mother collapsed onto the ground, crying. Chad was Josh’s best friend, but the worst part for Josh was watching his parents.

“There is just nothing like watching a parent go through that,” Josh said later. “And I just can’t. I wouldn’t wish it on anybody.”

That night, Josh and his parents stayed in a hotel nearby. His parents spent the night on the hotel phone calling family and friends to break the news. Josh’s dad gave him the phone for a minute and he called his best friend, Aaron, because he and his brother had all grown up together. Aaron had already heard the news from his mom. When he picked up the phone they just both started crying.

“I’m sorry,” Aaron said. He just kept saying, “I am sorry.”

In the morning, Josh and his parents walked into to Chad’s dorm room to collect his wallet, suit to be buried in and other things they needed to get through the next few days. The first thing they saw in the room was his books open on the desk. Chad had been studying before he left for the bonfire.

Josh sat in his brother’s old computer chair for no more than 5 minutes before he had to leave because he just didn’t want to be there anymore. He grabbed a stuffed penguin, named Linux, and went to sit in the parking lot. The penguin had been important to Chad. Josh kept Linux with him for most of the next four years.

When his parents finished packing, they drove home where family waited. While happy the house was overrun with people supporting his parents, Josh prefered to be anywhere else. Aaron drove Josh to his house where they were met by both of their girlfriends.

The four friends spent most of the time for the next few days at Aaron’s house leaning on each other and supporting one another.

Twenty years later, Josh’s parents still make sure there are flowers out on Chad’s grave at the Bourland Cemetery in Keller. Twenty years later, Josh is the head choir teacher at Legacy. Twenty years later, Josh doesn’t go to the memorial on the Texas A&M campus.

“I guess to me, I mean it is a lot of bad memories, obviously, but also it was a preventable tragedy,” Josh said. “There was a lot in that tradition that people [in the university] knew were dangerous and they just kind of allowed it, and I just don’t like going there because I don’t want to support what the university allowed to happen.”

The bonfire was an over 90-year-old A&M tradition. Before the UT game, student volunteers would build a 60-foot woodpile with over 5,000 logs, usually into late hours in the night. Then the whole A&M community, up to 70,000, would rally behind the blaze.

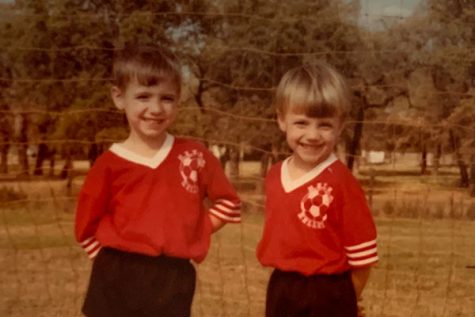

To remember his brother, Josh thinks about the time he spent with him in high school playing in a band and on the football sidelines as an honor guard. But he knows his parents continue to hurt.

“I don’t think that that’s a hurt that ever goes away as a parent,” Josh said. “And I think I get it more now that I have a child. I just can’t fathom the pain of watching a child die or losing a child like that. I mean everybody carries on. They’re great and they’re happy in their life, but I know that it’s still painful for them to think about it.”

Josh’s parents believe the traumatic experience changed their perspective and appreciation of life.

“Twenty years later, I am not going to lie. Some days I am just sad all over again that is one thing that time really doesn’t heal, but you do get better and you can smile at things instead of cry when you think of it,” Jill Powell said. “I will always miss him. Losing a child like that is life-altering.”

“I would never want to lose the times that sometimes you just get really sad and you miss him and you think about all the things you used to do,” Greg Powell said. “I don’t ever want to lose that because I don’t ever want to lose all of those memories. And as long as we still have those memories then he is still with us.”

Greg and Jill say the grieving process is not a quick one, and it took years to let themselves be happy again. Now they say they are doing well. Their faith and having no regrets about the life they lived with Chad kept them sane in the years following his death.

“[Chad] had such a great love for life,” Jill Powell said. “The biggest diservice we could do to him in death was to quit living. He would hate that. We have to pull ourselves together and go on. I think we have all done the best job we are able to do with that and he would like that.”

Josh doesn’t allow the tragedy to make him sad anymore, but he makes a point to tell his 11-year old daughter, Emmie, how exceptional of a person her uncle was.

“[Chad] affected and touched a lot of people’s lives,” Josh said. “So it is important for me that she knows who he was, and, like I said, sometimes I just I look at her and I think. I don’t know how I would carry on if something were to happen to her. It’s hard to think about.”

Josh remembers Chad for all of his best qualities and will tell anybody who wants to know just how amazing he was.

Choir director Josh Powell conducts the choir Christmas concert at Willy Pigg.

“He was two things: he was a genius. Certifiable, 100-percent genius, but he was also just one of the most caring people for everyone. He was the kid that a new person walks into school and he immediately makes friends with them or even somebody that he just sees that may be struggling that day like he just had an eye for this person needs someone to care about them and he just did, unfailingly. That’s why I think there were so many people at his funeral; I mean he just had a way of impacting people that he was around.”

Twenty years after Josh lost a bandmate, a brother and a best friend, he does the best he can to be like the person Chad would have been.

“I think I am not as good at it as he was, but I try to care about people,” Josh said. “I try to make sure everyone feels like they are valuable. That’s one of my main goals as a teacher to make kids know that I see them for who they are and wherever and whoever that may be, it’s ok. That’s something I learned from watching him. Wherever you are in life, it’s ok to be there.”

Theresa Proctor • Jan 10, 2020 at 4:43 pm

Fabulously written story, Ryland. You did a great job covering a difficult topic with sensitivity and grace.

Ed Larsen • Jan 10, 2020 at 2:18 pm

Ry,

Thank you for capturing the essence of family grief following loss in your story, “Living after loss.” I can empathize with Greg Powell’s comments about never wanting to lose the memories of a deceased child. Parents who lose a child want others to understand this. It can be uncomfortable for those outside the family to bring up the topic of a lost loved one, but the family members usually appreciate the opportunity to talk about that son or daughter who has passed. It helps with the ongoing grief and healing.

Thank you for writing a story that illustrates that so well, and may God bless the Powell family.

Ed Larsen

Cinco Ranch High School

Katy, TX

Donna seidmeyer • Jan 10, 2020 at 7:30 am

That was a supurbly written article. I loved it as it was told from such a personal and emotional angle. Job well done. Looking forward to the next one. You are really talented.